Revenue streams at banks and credit unions are taking a hit as the coronavirus impacts consumers’ spending patterns.

Governors across the country have closed or limited the operations of nonessential businesses, and travel has been sharply curtailed amid the pandemic. Because of that, consumers are using their credit and debit cards far less.

That will have a significant impact on interchange income for many financial institutions.

“Should credit unions be concerned about interchange income? Yes, they should,” said Glynn Frechette, senior vice president with Advisors Plus at the payments credit union service organization PSCU. “It would be irresponsible to answer that with a hard no.”

Global payments revenue totaled $2.3 trillion in 2018, the most recent data available, according to the Perspectives Report from consulting firm Sievewright & Associates. The majority of that comes from interest institutions earn on credit cards, though interchange and other fees constitute about 35% of that total.

Total revenue had been growing by about 8% annually over the last five years, and many observers expected it to increase by between 6% and 8% in 2019, according to Mark Sievewright, founder and CEO of Sievewright & Associates. But COVID-19 is likely to reverse those fortunes for 2020. Now revenue from payments could decline by 8% to 10%, or somewhere between $180 billion and $230 billion, Sievewright said.

As much as 80% of that decline could come from a decrease in interchange, as opposed to a drop in interest income, Sievewright said. That’s because consumers are unlikely to change existing habits, meaning those who don’t pay off their credit cards each month will continue with that pattern, resulting in continued interest income for those institutions, he added.

This hit will probably be more severe for some institutions than others. The nation’s top seven credit card issuers — JPMorgan Chase, American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Capital One, U.S. Bank and Discover — control roughly 78% of the market, Sievewright said. So any impact to interchange income will be predominantly felt by them.

Still, credit unions tend to be much smaller than their banking counterparts. Only about 6% of all CUs had $1 billion or more in assets in the fourth quarter, according to data from the National Credit Union Administration. That means most of the industry falls below $10 billion in assets, the threshold where the Durbin amendment kicks in.

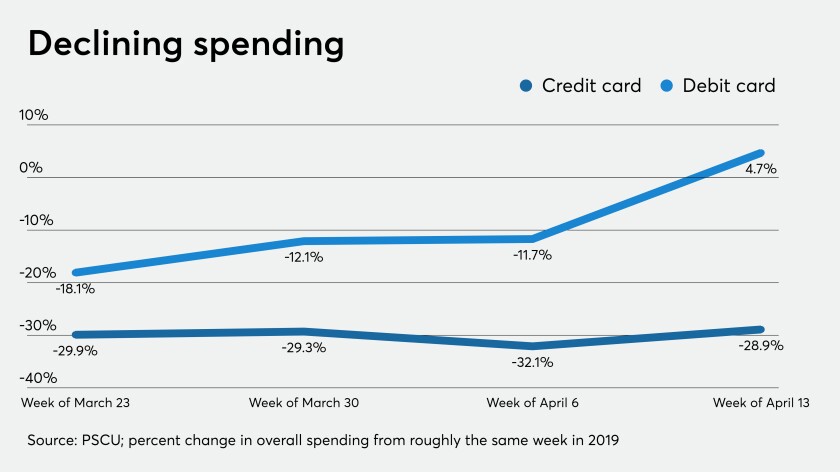

The pandemic also has consumers pulling out their credit and debit cards less frequently since measures such as widespread business closures and stay-home orders were put in effect to slow the spread of the outbreak. Overall spending for credit cards was down almost 29% for the week of April 13 compared with roughly the same week in 2019, according to data from PSCU.

“I think you can do things amid this crisis that puts your card top of mind for your customers or members,” Sievewright said. “But when a large portion of the places we shop at or do business with [are] closed, it’s very challenging to make up all of that lost revenue.”

Old National Bancorp in Evansville, Ind., reported during its first-quarter earnings call last week that several types of fees were under pressure from the economic downturn related to COVID-19. That included a sharp decline in overdraft and interchange during the last week of March, “as consumers began to comply with shelter-in-place orders and limited their spending to essential services,” Brendon Falconer, chief financial officer, said during the call.

Debit card and ATM fees, which include interchange, totaled roughly $5 million, down 9% from a year earlier, while service charges on deposit accounts slipped about 7%, to $10.1 million.

Many Americans are usually traveling this time of year, but those plans have largely been scrapped, meaning consumers won’t be using their debit and credit cards to pay for those expenses, Jim Ryan, chairman and CEO of the $20.7 billion-asset Old National, said in an interview.

“I think there will be pent-up demand that will hit when each part of the economy reopens,” Ryan said. “But there will be some losses. I usually get a haircut every three weeks. I won’t make up for the one or two haircuts that I missed.”

New consumer behaviors emerging?

Some factors could help blunt the decrease in interchange income. For one, stimulus programs could help spur spending.

Debit card spending was up almost 5% for the week of April 13 compared with roughly the same week a year earlier, according to PSCU data. The average amount of a debit card purchase increased almost 26% from a year earlier, and ATM withdrawals shot up about 18% from the prior week, PSCU said.

Drive-thru is almost synonymous with fast food, but for some quick-serve chains — like Subway — a past emphasis on in-store dining meant a much sharper pivot when the coronavirus pandemic struck.

Accounting firms Crowe LLP and BKD LLP released year-end tax-planning guides Wednesday, during a time of great uncertainty over future tax changes in the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the upcoming election.

Revenue dropped 6 percent as the pandemic triggered economic shutdowns across the country, according to data from 44 states compiled by the Urban Institute.

That’s because the Internal Revenue Service started sending out stimulus checks to Americans in mid-April, giving a boost to household income.

Sound Credit Union in Tacoma, Wash., had experienced a 15% to 20% drop in member spending but noticed that ticked back up for about five days as consumers received relief payments from the government, said Chief Financial Officer Troy Garry. But now the institution is seeing this fall once more.

“People were buying necessities,” Garry said. “But now we are starting to see spending kind of come back down.”

Old National saw larger declines in interchange in March, but spending picked up in April, Ryan said. Overall, the bank hasn’t seen customers’ incomes impacted as much as many expected. That could be because of government programs put in place to reduce the pandemic’s economic impact, such as enhanced unemployment benefits for those who have lost jobs.

Institutions hoping to spur consumers to use their card over the competition may want to consider rewards programs or other offerings that push their plastic to top of wallet, Frechette said. For instance, restaurants in many states are limited to providing only take out or delivery services so an institution may want to design a card incentive program around that, he suggested.

The $1.9 billion-asset Sound Credit Union is currently offering zero percent interest on purchases and balance transfers to its credit card through June 30, Garry said. The offer was initially put in place to help members who are financially struggling but it could also work to boost the credit union’s interchange income.

Normally Sound earns about $10.5 million a year from interchange fees, but its modeling indicates that figure will drop by about 15% for the year, Garry said. Even as businesses start reopening, consumer spending patterns could be altered for the foreseeable future.

“With unemployment being where it is at, it’s what percentage of these workers will get back to work,” Garry said. “I anticipate [spending] should go up from where it is, but will it be what we expected for the year? No. I think people could change their behaviors. Will people even go out and eat? Or did they enjoy eating at home and saving the money?”