WASHINGTON — The Federal Reserve’s cap on shareholder payouts by big banks immediately launched a second-guessing game within the banking industry, with many holding out judgment until the path of economic recovery from the pandemic is more certain.

In the publication of its annual stress-test results, the Fed said it would require big banks to suspend share repurchases during the third quarter and limit dividend distributions to the levels banks paid out in the second quarter. Those distributions could also be limited further, the Fed said, depending on each individual bank’s earnings results.

The central bank is also requiring the 34 banks with more than $100 billion of assets that it tested to resubmit their capital plans later this year.

As part of its normal stress-testing cycle, the Fed also tested banks against hypothetical economic models of recovery from the pandemic as a supplemental exercise to its typical stress testing regime to account for the impact of COVID-19 on bank capital.

While the results of those “sensitivity analyses” showed that banks would maintain the regulatory minimum capital requirements under different levels of economic stress, several banks were said to have approached the 4.5% minimum common equity Tier 1 capital requirement under the most severe scenarios. That revelation raised questions about whether the Fed should be doing more to ensure that banks hold onto capital.

“The board ended up taking a middle position of modest restrictions now while expressing caution about the future,” said William Lang, managing director at Promontory Financial Group. “This runs somewhat counter to the lessons of the last crisis, which were that it was preferable to conserve capital while banks are in a stronger position.”

Michael Barr, who worked on the Dodd-Frank law as former assistant secretary for financial institutions at the Treasury Department under the Obama administration, said that the central bank should have barred dividends altogether, like the agency did for stock buybacks.

He added that the analysis done for justifying continued dividends was too backward-looking and did not take into account the possibility that the economy has not yet even hit the recovery stage as some areas are dealing with a surge in new COVID-19 cases.

“We’re in the middle of an absolutely unprecedented global pandemic and economic collapse,” Barr said. “It doesn’t make sense to me. Now is the time that you want banks to raise additional capital to make sure they are even more resilient. At a minimum, the Fed should not be permitting dividend payments.”

That sentiment was echoed by Fed Gov. Lael Brainard, who voted against allowing banks to continue paying dividends to shareholders, saying in a statement that she did “not support giving the green light for large banks to deplete capital.”

But others viewed the Fed’s actions as judicious, and felt that the regulator went plenty far in ensuring that banks will be able to withstand a downturn of any scale.

“It’s hard not to look at what the Fed did and view it as prudent,” said Darren King, the chief financial officer of M&T Bank in Buffalo, N.Y., one of the banks tested against the Fed’s scenarios.

King would not say whether the Fed’s actions change anything about the $124.6 billion-asset bank’s own plans for buybacks or dividend payouts, but he did say the decision to cap dividends will either be prudent or “with any luck, the pain of the pandemic won’t be as severe and balance sheets will be strong and ultimately we will have excess capital to distribute to shareholders at a later date.”

Banks will be able to disclose their stress capital buffer requirements and planned capital distributions on Monday after the markets close, if they choose to do so. But because banks will need to go through another round of stress testing later this year, some are still weighing whether to release that information.

King said M&T Bank is undecided about whether it will report any stress-test information on Monday.

“We’ve got our stress capital buffer number, but we’re going to go through another process basically in 90 days and in the interim we know we can’t buy back stock or change dividends other than to decrease them,” he said. “So I’m not sure what else there is to say, and therefore I’m not sure if we will say anything at all.”

The Internal Revenue Service said Friday it would restart issuing its 500 series of balance-due notices to taxpayers later this month after they were paused on May 9 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The leaders of Congress’s main tax-writing committee are wondering if the Internal Revenue Service will be ready to handle next tax season as it’s still processing millions of pieces of correspondence that went unopened for months during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Internal Revenue Service is reversing course on the automatic revocation notices that it sent to more than 30,000 tax-exempt organizations.

Wells Fargo, Citigroup, U.S. Bancorp, Fifth Third Bancorp and Citizens Financial Group declined to comment on the Fed’s decisions. In March, as economic uncertainty mounted, all five were part of the group of banks that temporarily suspended share repurchases through at least the end of the second quarter.

Because the Fed did not disclose how individual firms performed in the sensitivity analyses and instead published the results in aggregate, many were left guessing as to which banks performed better than others.

That could play into bank decisions on whether to publish their stress capital buffer requirement next week.

That buffer, which was finalized in March, calculates a bank’s stress capital buffer as the difference between a bank’s starting and projected capital ratios under the “severely adverse” stress-test scenario, and factors in a bank's common stock dividends as a percentage of risk-weighted assets.

“My best guess would be that most banks will feel the need to disclose the stress-capital buffer themselves,” said Lang. “Holding back on disclosure might lead market participants to infer that there is a problem even though banks are in a strong capital decision. This could be worse than a bank reporting stress-capital buffers that are larger than its peers.”

The Fed’s decision not to disclose how individual banks fared under its hypothetical coronavirus-related scenarios was met with criticism from many who felt that the sensitivity analyses lacked transparency. Barr called that decision a “mistake.”

“It didn’t make sense to hide details of the individual firms,” said Barr, who is now dean of the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. “The stress tests were a lot less useful than they should have been in helping us understand the health of the financial system.”

In a speech last week, Fed Vice Chairman for Supervision Randal Quarles explained that the Fed decided to release only the aggregate results of banks tested partly because the agency did not give firms advance notice about the scenarios it would be testing the firms against.

“I don't think the Fed wanted to use that sensitivity analysis in a public way to address any one firm,” said Adam Gilbert, a partner at PwC. “I also think they would not necessarily want to single anyone out related to the pandemic sensitivities, because that can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, so you want to be careful about that.”

Meanwhile, some industry observers were hoping to get more clarity from the Fed about capital plans and the pace of future dividend payments. Instead, the central bank is going to monitor capital plans every quarter even as new capital plans are approved.

That means “questions about dividends are going to remain an overhang” and the resubmission of those capital plans could be a negative sign for dividend payments beyond the third quarter, said Brian Kleinhanzl, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods who covers big banks.

Kleinhanzl said he doesn’t expect the Fed to release new scenarios until late in the third quarter or make decisions about the resubmitted capital plans until after the November presidential election takes place.

What those scenarios ultimately look like remains unknown for the time being.

“What happens in the economy between now and [later in the third quarter] is of utmost importance,” Kleinhanzl said. “That will have some influence on how stressful these scenarios are.”

Analysts at Robert W. Baird and Co. said in a note to clients Friday that the Fed is likely to keep a “short leash” on any dividend plans submitted by the banks going forward. Baird analysts expect most banks will hold dividends at the status quo, but they said “a dividend cut seems likely” for Wells Fargo.

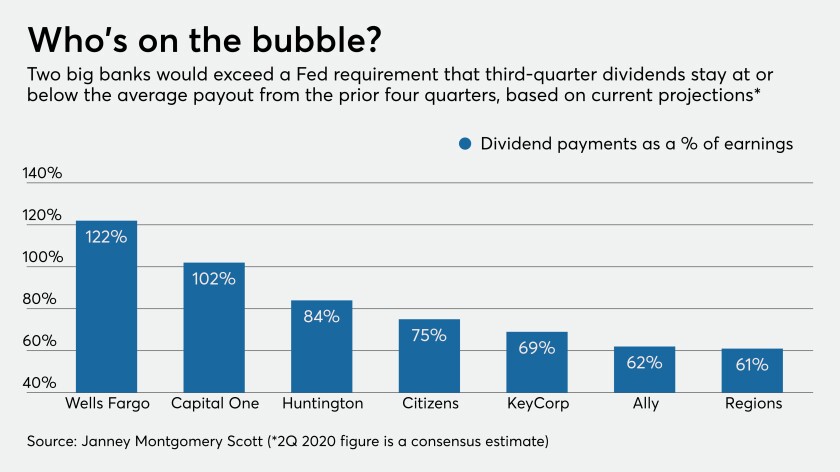

Wolfe Research analysts along with analysts from Janney Montgomery Scott calculated that only two banks, Wells Fargo and Capital One, currently had dividend levels above what the Fed would permit and stood the highest chance to make cuts.

"While bank dividends appear largely safe for now, we would note that the group has not yet been given the 'all clear' as limitations will be revisited on a quarter-by-quarter basis," the Wolfe Research analysts wrote.

The Fed’s message regarding dividends is clear, said Christopher Marinac, an analyst at Janney Montgomery: Current earnings at individual banks have to support current dividends payouts.

“It’s kind of like the Fed is reminding us of what we really should be focused on — what are the current earnings and where are we with this recession?” he said. “And right now it’s very open-ended.”