That JPMorgan Chase is preparing for a possible surge in defaults was to be expected, but the numbers are still breathtaking — and the calculus behind those figures is telling.

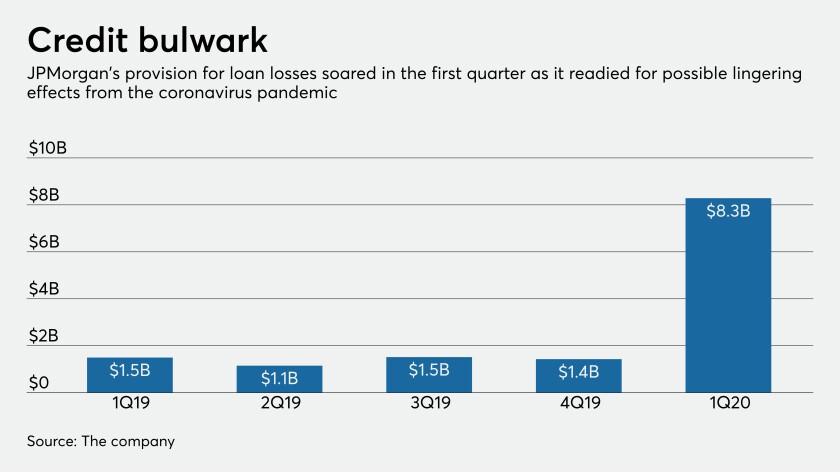

The bank’s first-quarter provision for credit losses was nearly six times larger than in the fourth quarter, which was weeks before the novel coronavirus shook the U.S. economy. Moreover, executives warned Tuesday they are preparing for the possibility of a worst-case scenario in which the economy remains closed longer than expected and the bank’s credit costs could exceed $45 billion.

The largest U.S. bank by assets and the bellwether of Wall Street was the first to report earnings in the face of the global pandemic. Its 69% plummet in profits and its economic outlook are expected to resonate with all banks, which are tasked with buttressing an economy in standstill while protecting their own balance sheets.

JPMorgan Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon urged the establishment of a safe plan to get U.S. workers stuck at home back to work — but only after a go-ahead from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and after there is enough hospital capacity and testing for the virus.

“You have to get that done,” Dimon said. “A bad economy has very adverse consequences way beyond just a bad economy.”

While controversy swirls around when businesses should open their doors again, and who can make that call, Dimon indicated May would be too early.

“We’re talking about June, July or August, something like that,” Dimon said.

Professional services like accounting and tax prep gained 12,000 jobs, however, according to the payroll giant.

The recent stimulus law’s relief for renters and extension of the federal eviction ban were meant to ward off a housing crisis. But owners of 1- to 4-unit dwellings still face mounting mortgage and property tax debts, and delinquencies could start rising soon — followed by foreclosures.

The relief bill includes an extension of the 45Q tax credit, which gives companies a tax break for capturing carbon..

Perhaps in a sign of the serious risks facing the economy, Dimon spoke more on the bank’s first-quarter earnings call, and deferred less to his lieutenants, than he had in recent years.

His presence on the call was significant for another reason. He had emergency heart surgery in March, and co-presidents Daniel Pinto and Gordon Smith ran the bank in his absence. Dimon said as markets started to gyrate while the spread of the COVID-19 worsened, he was eager to get back to work.

Christopher Marinac, director of research at Janney Montgomery Scott, said that Dimon’s announcement that he was back in the CEO position in early April might have contributed to a rally in bank stocks at about that same time.

“Jamie back-in-the-saddle is absolutely reassuring for investors,” Marinac said.

JPMorgan set aside nearly $8.3 billion in provision for credit losses for the first quarter, up from roughly $1.5 billion in the same period last year and $1.42 billion in the fourth quarter.

In figuring out how much to set aside, the bank relied on a forecast from its economists, who expect unemployment to reach 20% but start to recover in the second half of the year, Chief Financial Officer Jennifer Piepszak said. However, U.S. GDP is likely to continue to sag from where it was to start 2020, according to that forecast.

The bank also factored in Congress’ stimulus programs and its own relief given out to borrowers in estimating what to set aside in the first quarter. Piepszak mentioned the possibility of further stimulus coming from Congress in the next month that could strengthen the bank’s bottom line as well. Complicating matters, however, is the new Current Expected Credit Losses accounting standard that requires banks starting this year to set aside reserves for potential losses over the life of their loans.

Analysts at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods expect JPMorgan’s total provision for credit losses in 2020 will be $23.6 billion. Barclays Capital analysts estimated that half of the first quarter’s reserve build was for CECL’s new requirements.

So far, the bank says it has seen little deterioration in credit quality as it extends new credit, works with struggling borrowers and facilitates the government’s emergency programs.

Customers have asked for forbearance on about 4% of JPMorgan’s total book, Piepszak said.

As the economy began to shut down to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus, corporate clients drew down on their revolving credit lines at about 10 times the rate seen during the 2007-8 global financial crisis, Dimon said.

The bank’s clients have drawn more than $50 billion in revolving credit lines, and the bank approved another $25 billion in new credit extensions in March alone, according to financial documents. Overall, commercial and industrial loans for the bank were up more than 26% year over year because of the draws.

Banks have so far been able to handle the demand for credit line draws despite speculation they could use certain contractual language to shut off new financing if the downturn worsened.

JPMorgan also helped clients access more than $380 billion from debt markets in the quarter in what Dimon called the biggest quarter for investment-grade debt the bank has ever seen.

Piepszak said there has been a slowdown since then and that the bank expects draws to continue at lower levels than the initial rush going into this crisis.

“People got scared and got scared quickly and wanted to make sure they have liquidity,” Dimon said.

JPMorgan has 300,000 applications in some stage of the approval process for the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, involving about $37 billion in loans, Piepszak said. The bank has so far funded $9.3 billion of these loans.

The program was rolled out on April 3 to facilitate $349 billion in loans to help small businesses cover employee salaries but was soon overwhelmed with snafus and uncertainty. Banks faced a stampede of applications and, largely, elected to dole out funds to their existing borrowers first. But Dimon said Tuesday the program has been a success despite the early problems.

“For a program like that to be rolled out at that speed by the banks and the government is kind of exceptional,” Dimon said. “You can quibble with the fits and starts of it ... but I think it’s kind of exceptional that the government can move that quickly and that effectively.”