Millions of Americans have already received their economic relief payment from the government, and millions more will be receiving it in the coming weeks, in an effort to stave off severe financial woes amid the coronavirus pandemic.

But whether these checks provide much-needed relief will depend, at least in part, upon actions taken by financial institutions.

When money is deposited into checking accounts, banks determine how much of that money is immediately available to the consumers to spend. Banks generally operate under the premise that if the customer owes them money — like having overdrafted an account, for example — the bank will first reclaim that money off the top, along with any fees due to the overdraft.

Similarly, to the extent that there are past-due payments on a loan, banks can claim that payment, along with any late fees, before making relief funds available to the consumer. Further, some banks have structured loans as “deposit advances” so that payments become due and are automatically clawed-back whenever money is deposited.

Even having a more conventional loan with regularly scheduled payments, as soon as the payment comes due, banks may be able to put themselves first in line to quickly grab money from consumers’ accounts. Indeed, with modern technology creditors who do not even have a banking relationship with their customers may still be able to monitor banking accounts in real time and fuel a race to get repaid as relief-check deposits arrive.

Through the coronavirus aid bill, Congress protected these relief checks from claims for debts owed to the federal or state governments, and some states have provided protection from garnishment or attachment as well.

However, Congress did not shield the money from private claims. And it is unclear whether state actions apply to self-help measures by banks. Indeed, Treasury officials have reportedly advised banks to make “business decisions” about whether to skim money from the recovery rebates to repay loans and fees. Absent government action, many consumers will be affected by these business decisions that will determine how much damage the coronavirus does to their financial health.

Small-business employment and hours worked grew a bit in September, especially in the Northeast and within the construction industry, according to the latest monthly report from payroll giant Paychex.

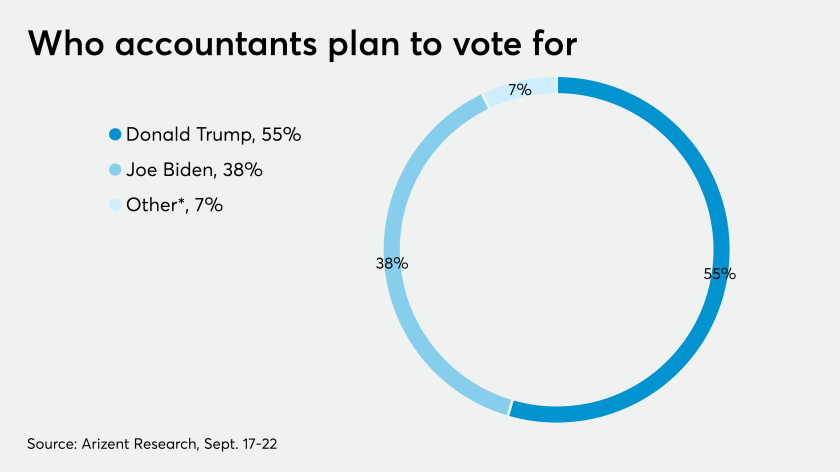

Regardless of their voting intentions, they overwhelmingly expect things to improve after Nov. 3.

The shutdown in March forced O&G firms to confront the inefficiencies of their financial processes.

Even before the coronavirus national emergency, a sizable portion of Americans were financially vulnerable and an even larger group were barely coping financially. For example, research conducted by the Financial Health Network found that 27% of adults had already skipped needed medical care because they could not afford it, and 34% were unable to pay their bills on time in a 12-month span from 2018 to 2019.

An even larger group, at 48% of the adult population, reported lacking sufficient liquid savings to cover three months of living expenses. Many of these Americans will need every dollar of their recovery rebates to meet their basic needs.

Financial institutions concerned with their customers’ financial health — as they all should be — would do well to heed Hippocrates's edict, “First, do no harm.” This means, at minimum, banks should refrain from taking money off the top for negative balances, past-due loan payments and penalty fees. Beyond this, during the period of the national crisis, financial institutions should place a moratorium on charging such fees as well as on aggressive collection tactics, such as repossessing automobiles.

Some financial institutions have made a promising start by providing consumers with full access to their relief funds and imposing moratoria on certain penalty fees for limited periods of time. But more is needed to avoid magnifying the financial devastation of this crisis.

Financial institutions should follow the lead of selfless medical providers by responding to the crisis in ways that will ease financial pain and help consumers along the road to recovery. This means working with customers who, through no fault of their own, cannot afford to make monthly payments on their loans. In response, lenders should adjust the terms as needed.

Congress already has mandated forbearance for federal-backed mortgages and most (although not all) federal student loans. However, relief bills have left out hundreds of millions of consumers with auto or credit card loans. For these consumers, financial institutions have a critical role to play in working with their customers to arrive at arrangements that provide immediate sustainability and until the crisis has abated. Many institutions have announced their willingness to do so.

In times like this, liquidity becomes a key need for many. Some institutions have announced plans to waive limits on withdrawals from savings accounts and penalties for early withdrawal of CDs. Unfortunately, many consumers lack such savings to fall back on. And in a time of economic contraction, credit tends to tighten precisely when it is needed most.

Federal regulators have recently encouraged financial institutions to offer so-called “responsible small-dollar” loans. In doing so, the regulators seemed to have blessed what they call “appropriately structured single-payment loans.”

The Financial Health Network has long championed well-designed, quality small-dollar loans. But such loans should be affordable and structured to support repayment without reborrowing. For example, U.S. Bank’s decision to reduce the annual percentage rate on its 90-day, small-dollar installment loans is an encouraging development.

During this time, it is also important to acknowledge the costs that the financial sector will incur. No matter how well the government succeeds in directing relief to hard-hit consumers, there will almost surely be a significant increase in credit losses.

Placing a moratorium on auto repossessions could add to those losses. Moreover, by forgoing penalty fees and reducing interest rates to accommodate struggling consumers, financial institutions will be foregoing revenue that could be used to offset these losses. Even at a time of record-low interest rates, this may be especially difficult for small financial institutions serving low- and moderate-income families, as well as the emerging fintech sector. The nation should be mindful of institutions that provide such help.

Some financial institutions are taking actions to protect their customers’ financial health at the cost of not returning profits to shareholders in the near term. But those customers will always remember the bank was there for them in such a critical time of need.

For those playing the long game, there is a strong business case for prioritizing customers’ financial health during this crisis.

This is a time when the first priority of the financial system must be to attend to consumers’ financial wellbeing as well as for the sake of the nation’s health.