In 2011 Evelyn Forget, a health economist at the University of Manitoba, unearthed the dust-covered files of a long-forgotten payments experiment.

From 1974 to 1978, the poorest residents of Dauphin, a small Canadian prairie town, had received monthly support payments from the provincial government. The idea had been to see whether providing a basic income could improve education and health outcomes for the most vulnerable in society. The initiative ran for four years before being scrapped amid the political turmoil of the late 1970s before the data could even be analyzed.

It was one of the first basic income experiments in the world. Now more than 40 years later, the findings from this and other studies are adding weight to calls for nationwide basic income schemes to be introduced in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic.

In the U.K., many policy researchers predict that the economic fallout of the pandemic in the U.S. could change attitudes toward the idea of basic income on both sides of the Atlantic. While U.K. politicians have traditionally been skeptical about the concept, citing the vast administrative costs of both processing the number of payments, and identifying eligible recipients, there are signs that the mood is changing. At the end of April, more than 100 opposition MPs and peers called on the government to introduce a recovery universal basic income — involving regular payments to all adults in the country — in the months after the lockdown ends.

“What happens in America will change attitudes and policy all around the world,” said Alan Lockey, head of the RSA Future Work Centre in the U.K. “People losing jobs will mean they lose their health care insurance, and they haven’t got as much of a safety net as we have. I think this will push them towards some radical solutions.”

The evidence from past studies suggests that a basic income could have some profound societal benefits. Over the past nine years, Forget has analyzed the results of the original Manitoba experiment, and found that the scheme reduced hospitalizations by almost 9%, as well as enabling more people to complete high school and go on to further education. A recently completed study in Finland, which gave 2000 unemployed people a monthly basic income for two years, found that the security helped individuals move from part-time contracts into full-time work, and become more independent from the state.

“I think that there’s a lot of rationales for this kind of scheme in the wake of COVID-19, which has shown that the existing social programs we have in place are not up to the task,” said Forget.

The document discusses some considerations involving the use of specialists when auditing financial statements during the pandemic.

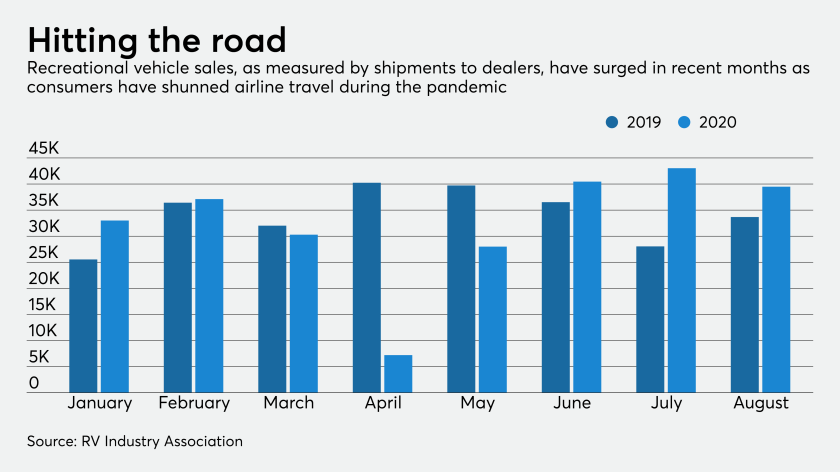

Many consumers are taking to the highways and the water for safe getaways during the pandemic — powering one of the few bright spots in lending. However, bankers warn that boomlets usually come with distinctive credit risks.

Conversations have already started about how the increased government expenditures to support citizens during the pandemic will be funded. But resisting the urge to increase taxes may be the best way to support economic growth.

However, a basic income scheme has never previously been implemented on anywhere close to a national scale, which presents vastly different challenges in terms of administering and financing such a project. In 2017 Luke Martinelli, a researcher at the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath, published a report estimating that the gross fiscal cost for the U.K. would range from £140 billion to £427 billion, depending on the weekly payment level and structure.

Most economic models predict that this could be funded either by changes to the taxation and existing benefits systems, but Martinelli points out that corporation tax hikes or substantial benefits cuts could lead to more problems.

“Corporation tax changes could affect behavior by making investment less profitable,” he said. “In other words, it could restrict supply of capital. If all benefits were to be eliminated, less extensive tax rises would be required — but these types of scheme are either very expensive, requiring high payment levels to replace the existing provisions, or they tend to increase poverty and make poor families worse off. The most feasible option would be a modest basic income payment, with other means-tested benefits remaining in place as top-ups. You could do this by eliminating the personal income tax allowance, harmonizing national insurance contribution rates, and raising income taxes by a few percentage points.”

There are two forms of basic income that are typically broached. One is a universal approach, which involves sending equal payments to everybody with an increasing portion returned through taxation for higher earners. The other is called a negative income tax, where only those earning below a certain income threshold receive any payment.

However, Greg Mason, an economist at the University of Manitoba, predicts that if any such scheme is introduced on a national scale by any government in the near future, it will more likely be the latter due to the sheer administrative burden of making payments to everyone.

In the eyes of Mason and other economists, for a negative income tax scheme to work on a population level, it is necessary to find the right payment threshold to ensure there is always an incentive to seek full-time employment. Mason predicts that such a threshold is likely to be in the region of CA$15,000 per year.

“Basic income is going to work as long as people understand that it’s the equivalent of rations,” he said. “This is not allowing people to live the good life; it is survival. The reason why that is so important is because if you are too generous, you will undoubtedly create problems in terms of people’s willingness to work. The trick is finding that spot where you give enough, but you also make sure people see that there is always value to working.”