At Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital, the frustration is easily apparent. There’s tons of activity, but these are far from good times.

The hospital needs new technology to handle the transactions that support its business. But it’s not possible right now because of the scale of the coronavirus outbreak.

“No new IT technology is being implemented at this time. In fact, our [software upgrade] project has been delayed due to the pandemic,” said Kathy Peterson, vice president of revenue cycle for the Plattsburgh, N.Y.-based hospital, in an email exchange.

Like other businesses, the hospital has been forced to make instant emergency changes because of the coronavirus. But many hospitals are concurrently getting a rush of demand for service with an unclear revenue stream. The stories of how dangerous this work is for health care providers are well told. But behind that, there’s also an uncertain path toward tracking how the services will get paid for, and how to process these payments.

While the federal government has said it will fund coronavirus treatment for uninsured patients, the reality is far more complicated. The government’s promise makes undetailed mention of not covering “unexpected charges.” There are added complications for private insurance plans that create confusion over what’s covered, who is getting the bill and making the payment, and what actually constitutes coronavirus treatment.

“Copay collections at the time of service have virtually stopped due to the outpatient volume coming to a screeching halt and we don’t know if emergency room visits are COVID-related or not, so the potential that a copay would be waived is preventing us from collecting anything in this environment,” Peterson said, noting that since it is an upstate hospital (Plattsburgh is about 300 miles from New York City), the conditions comparatively aren’t as bad as they are downstate.

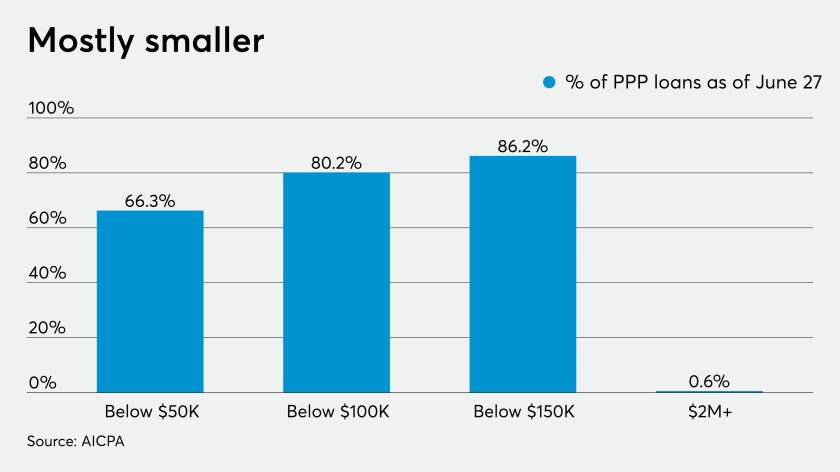

As the time comes for businesses to apply for PPP loan forgiveness, CPAs can provide vital assistance to ensure success for their clients.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on Wednesday closed off chances that the Senate would pass anytime soon a House bill that would give most Americans $2,000 stimulus payments.

The initial direct deposits of the second round of economic impact payments are already going out to taxpayers.

New York and most other states have required hospitals to temporarily increase bed capacity with an eye on optimizing ICU beds, while canceling elective outpatient procedures and service (though New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in recent days said these elective procedures will resume soon at some facilities). This curtailment has caused financial stress on outbound claims and cash flow, according to Peterson. Billing staff are still at full levels, but billing will slow down until volumes of elective procedures ramp up again.

A new code

Hospital payments work in part on the codes that identify and track cases, and inform the complicated payment rails.

Health care is different from retail payments, in that there’s one or more third parties involved most of the time. So the insurance, or a government payer, picks up some portion of the care while the patient is responsible for the rest. The codes are designed to communicate and clarify these responsibilities.

“Typically with these codes, there’s a process around the industry to submit correctly,” said Michael Trilli, research director for Aite Group’s insurance practice. “Now this is happening all at once. It’s Herculean to think about what’s being done at hospitals, which are also doing this while providing a high level of care.”

An anecdotal look at these codes in play shows how quickly a payment stream can unravel. The COVID diagnosis codes only became effective on April 1, so any cases before that won’t have a specific COVID dx code, as all electronic systems reject that code, Peterson said.

When patients came for testing in the earlier scenario, the hospital didn’t bill for that test, since the lab provides that invoice, as well as the invoicing for the specimen fee. But the hospital routinely tests for flu A/B/rsv, and if that test comes up negative, the specimen is sent to the state lab for a COVID test.

“Unfortunately, as these are sent to the payers they are not recognizing these as ‘rule out’ COVID visits and are applying copays/deductibles,” Peterson said, adding the hospital is now performing tests in its own lab and will be able to bill for all components, making it easier to identify accounts, coding and insurance issues.

The Plattsburgh hospital has the ability to take payments through its website and other mediums, and plans to enable smartphone payments. Currently the hospital is utilizing technology that takes the balances from its disparate systems and allows the patient to make one single payment and disperse the money electronically to the different systems for both professional and hospital balances.

There have been some emergency staff relocations inside the hospital that have added further challenges.

“Staff that have been displaced are now working in other areas of the hospital such as entrances to the facility for screening,” Peterson said. “We have not had to ramp up in our call center at this time, where patients call in regarding their bills.”

Many hospitals are redirecting staff to accommodate a surge in patients, and that often includes reducing payment officers at just the time when a hospital needs them most, according to Beth Barksdale, CEO of Encore Exchange, a hospital payment services company.

“People in billing are being pulled off the phones and moving into registration to deal with people in a clinical setting” Barksdale said. “It’s an extraordinary change.”

That leaves a vacancy in which customer service struggles.

“Things will become more complex on the other side of this. Right now there’s just the historical challenge to code the information,” Barksdale said.

Deferred payments, deferred tech

Under the best of times, payment flows are hard for health care providers to manage, leading to a sub-industry inside the payments business to sell automation to providers that still manage about half of payments documentation on paper.

Adding a pandemic to the mix is a huge wrench.

The coronavirus crisis has tossed what had been an incremental trend into an instant chaotic response for health care providers. Hospitals and other facilities have been adding explanations of benefits, invoices, billing and payments to digital rails for years, but not fast enough to handle thousands of new patients with an uncertain method of payment.

“The payment rules have been designed on the fly for coronavirus, so how do you manage that?” Trilli said.

Given the urgency, the critical mass of the crisis has to wane before deeper automation can be tackled. The coronavirus case load has to decline and hospitals have to recalibrate to a more normal setting in which traditional surgeries and treatments with a predictable revenue stream are the majority of the business.

“It’s like what you’re seeing in other industries,” Trilli said. “There’s clearly a need for a better digital payment experience, but that’s a mid -to long-term problem. We’re in the middle of a crisis now.”